| Women Soldiers: The Historical Record |

|

Joshua S. Goldstein

More information about War and Gender is available at

www.warandgender.com

For the References cited in footnotes, click here

Abstract

The question of women soldiers has generated substantial historical research, but of mixed quality. This paper -- from a chapter of War and Gender: How Gender Shapes the War System and Vice Versa (Cambridge, 2001) -- comprehensively reviews the historical performance of women combatants in war, across history and cultures.

Women's participation in combat, although rare, demonstrates potential capability roughly equal to men's – though women on average may fight less well than men. Women have proven to be capable fighters in female combat units, in mixed-gender units, as individuals in groups of men, and as leaders of male armies.

Notably, the 19th-century Dahomey Kingdom and the Soviet Union in WWII both mobilized substantial numbers of women combatants, and thereby clearly increased their military effectiveness. Yet these successes were not copied elsewhere. Domestic political structures and ideologies appear central to the Dahomey and Soviet deployments of women soldiers. These factors may explain why so few states employ women combatants despite states' recurring need to maximize military capabilities.

INTRODUCTION

The question of women combatants has generated substantial historical research in recent years, sparked by feminist scholarship’s interest in uncovering the previously ignored roles of women in social and political history. Several accounts chronicle the role of individual women soldiers in a variety of societies and time periods. Historian Linda Grant De Pauw writes, “Women have always and everywhere been inextricably involved in war, [but] hidden from history…. During wars, women are ubiquitous and highly visible; when wars are over and the war songs are sung, women disappear.”1

Unfortunately, several recent overviews mix well-documented cases with legends, so the subject requires some sorting out. In particular, John Laffin’s 1967 Women in Battle contains almost no documentation, and the caveat that the stories therein were “difficult to acquire and even more difficult to verify.” (Laffin’s own opinion is that a “woman’s place should be in the bed and not the battlefield.”) Yet Laffin’s stories turn up as fact in Jessica Amanda Salmonson’s 1991 Encyclopedia of Amazons – a confusing mix of historical and mythical cases – and David Jones’s 1997 Women Warriors, among others. Linda Grant De Pauw is more reliable and provides good documentation on US and European history, despite accepting too uncritically some unsupported claims concerning prehistory, anthropology, and non-Western countries. De Pauw groups women’s roles in war into four categories: (1) the classic roles of victim and of instigator; (2) combat support roles; (3) “virago” roles that perform masculine functions without changing feminine appearance (such as warrior queens, women members of home militias, or all-female combat units); and (4) warrior roles in which women become like men, often changing clothing and other gender markers.2

The evidence on women soldiers and that on women political leaders in wartime seems to support liberal feminists; women can perform these roles effectively. I review women’s participation in each of several settings in turn – female combat units, mixed-gender units, individual women in groups of men, and women military leaders of male armies.

| |

| A. FEMALE COMBAT UNITS |

Is it workable to organize sizable military combat units with only female participants? The answer is a qualified yes – it has been tried only a handful of times in all of history, but the results show the possibility of success, defined as strengthening the military’s effectiveness in war. These cases, although few, demonstrate the possibility of effective women combatants.

Dahomey in the slave-trading era

The eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Dahomey Kingdom of West Africa (present-day Benin) is the only documented case of a large-scale female combat unit that functioned over a long period as part of a standing army. The Dahomey Kingdom arose in the late sixteenth century when an aggressive clan conquered its neighbors and expanded its territory. The economy of Dahomey was fundamentally based on the slave trade – go to war against neighboring societies to capture slaves; trade the slaves to Europeans for guns; use the guns to go to war. Interwoven with these wars were extreme acts of large-scale human sacrifice, torture, and cannibalism, practiced on prisoners captured in war. Dahomey was one of the most successful military organizations ever in its region, and was rightly feared by its neighbors. It grew up with the slave trade – which expanded after 1670 and eventually exported 2 million people from the area – and ended when France conquered it in 1892, at the end of the slaving era. The kings of Dahomey enjoyed showing off the Amazon corps to visiting Europeans (Dahomey’s slave-export customers) who were always interested in the phenomenon, and thus we have direct reports from English visitors in 1793, 1847, and 1851. Stanley Alpern has documented the case well.3

The “Amazon corps” appears to have originated in 1727 when Dahomey faced a grave military situation. King Agadja armed a regiment of females at the rear, apparently just to make his forces appear larger, and discovered that they actually fought well. Subsequently, the king organized the Amazon corps as a kind of palace guard. The corps’ size, which varied over time and is in some dispute, apparently ranged from about 800 women early in the nineteenth century to over 5,000 at the mid-century peak, several thousand being combat forces. Women comprised a substantial minority of the Dahomean army, varying from under one-tenth to over one-third of the total. Some of the women were native-born, while others were captured in war and showed surprising loyalty. In one instance, a girl who had been captured young and raised in Dahomey was recaptured while fighting in the Amazon corps but refused to go back to her parents, insisting on returning to Dahomey instead.4

The women soldiers were armed with muskets and swords. They drilled regularly and resembled the men in dress and activities (see Figure 2.1). They stayed in top physical condition and were fast and strong. In the field, the Amazon corps carried mats and bedding on their heads, along with powder, shot, and food for a week or two. Some writers describe the women as rather large and strong. However, this physique is common to the other countries of West Africa, none of which used women as soldiers.5

Figure 2.1 Dahomean Amazon, as drawn by English visitor, 1850. [Forbes 1851, plate 2. Smithsonian Institution Libraries. © Frank Cass & Co.]

The women showed at least as much courage as the men – more, by several accounts – and had a reputation for cruelty. There was no known case of women warriors fleeing combat, although men often did so. One European observer concluded that, “if undertaking a campaign, I should prefer the females to the male soldiers.”6

The women of the Amazon corps said: “We are men, not women!… Our nature is changed.” They dressed, ate, and behaved as the men did. The Amazon corps members were technically married to the King (but did not have sex with him), were extremely loyal to him, and were forbidden to have sex with men (at the risk of death for both, although some observers thought the rule was frequently broken anyway). Several thousand lived in the palace, along with civilian wives (perhaps 2,000 of them) and female slaves. According to one report, female prostitutes were employed in the palace to serve the Amazon corps, although this is unclear. The Amazon corps was totally segregated from men. Outside the palace, its approach was announced by a ringing bell. Everyone had to turn their backs, and males had to move away.7

The Dahomean army was not primarily female. Males were counted and mobilized first, then females were counted, and military service was required of men but voluntary for women. A village could send women in place of men who did not want to serve. The army was divided into two parts, the left and the right, and each was in turn divided into a male and female component – a division which somewhat reflected the organization of Dahomey political administration.8

Although not in the majority, the women soldiers played a key role in the Dahomey army, and performed admirably in combat. In a battle in 1840, an enemy force routed the male Dahomean soldiers and only a rally of the Amazon corps prevented disaster. Using female soldiers had some drawbacks, however. In 1851, 10,000 males and 6,000 females faced 15,000 defenders in a neighboring society. The defenders were “infuriated” by the discovery – as they were preparing to castrate a prisoner of war – that some of the Dahomean soldiers were women. They redoubled their efforts, with their own women acting as supply troops, and repulsed the Dahomey attack with 2,000 to 3,000 Dahomey killed. In 1890–92, France conquered Dahomey, but it required several bloody attempts (showing that Dahomey was the strongest military power in West Africa at the time). In the first major battle, in 1890, Dahomey women soldiers took part and several were found dead on the battlefield, to the surprise of the French soldiers. In a later battle, the French commander noted that the Amazon corps, about 2,000 strong, led the attack in the presence of the king and showed remarkable speed and boldness.9

Dahomey probably turned to women soldiers in part because, unlike its neighbors, it faced a severe military manpower shortage for three reasons. It was exceptionally warlike and lost men in war. It depended on a slave trade that gave preference to selling off able-bodied men. And it faced a hostile neighbor ten times larger than itself. Firearms had only recently been introduced to the region, but this does not explain the Amazons (by equalizing men’s and women’s strength) as Marvin Harris claims. Although muskets were basic weapons, they were crude and often ineffective. A machete-like sword was decisive. Women effectively used this and a variety of weapons including daggers, bayonets, battle-axes, bows and arrows, clubs, and a giant folding razor (with a blade over 2 feet long) apparently used mainly for decapitation but possibly for castrating enemies as well.10

Dahomey is a critical case because it shows that women can be physically and emotionally capable of participating in war on a large-scale, long-term, and well-organized basis. Far from being weakened by the participation of women, the army of Dahomey was clearly strengthened. Women soldiers helped make Dahomey the preeminent regional military power that it became in the nineteenth century. Yet Dahomey is virtually the only case of its kind. The puzzle is why this successful case was not emulated elsewhere.11

The Soviet Union in World War II

Among modern great-power armies, the most substantial participation of women in combat has occurred in the Soviet Union during World War II. Following a rapid, forced industrialization of the Soviet economy in the 1930s under Stalin, in which women were drawn into nontraditional labor roles, the Soviet Union faced a dire emergency when it was invaded by Nazi Germany in 1941. Over the next three years, the Soviets would count tens of millions of war dead, and large parts of their country would be left in ruins. In this extreme situation, the Soviet Union mobilized every possible resource for the war effort, eventually including women for combat duty. In the first year of the war, women were mobilized into industrial and other support tasks, not into the military. These tasks included those women were already doing – they were already 40 percent of the industrial labor force at the outset – as well as new occupations that had been all male, such as mining. Women also dug trenches and built fortifications for the Soviet military.12

Beginning in 1942, faced with manpower shortages, the Soviet Union drafted into the military childless women not already employed in war work. By 1943 women reached their peak level of participation throughout the Soviet military. Their main areas of involvement were in medical specialties (especially nursing) – these were often front-line positions – and antiaircraft units which “became virtually a feminized military specialty.”13

Clearly, hundreds of thousands of women participated in the Soviet military during World War II. However, sources “are distressingly vague” on the actual number. The official figures state that about 800,000 women participated in the Red Army and about another 200,000 in partisan (irregular) forces. These figures put women at about 8 percent of overall forces (with 12 million men). Of the total of 800,000, about 500,000 reportedly served at the front, and about 250,000 received military training in Komsomol schools. Most were in their late teens.14

All the information regarding Soviet women’s participation in World War II comes to us through “a mass of hyperbolic and patriotic press accounts and memoirs.” Playing up the contributions of women helped the formidable Soviet propaganda machine to raise morale in a dispirited population, and spur greater sacrifices by the male soldiers. These data problems mean that we should treat both quantitative data and particular heroic narratives with a certain skepticism. The “majority of women did not serve in direct combat.”15

Despite all that, clearly women participated on a substantial scale – hundreds of thousands of individuals, a nontrivial minority of the total forces. Even if we reduce the extent and heroism of female participation from the official version, we are left with an important historic case of large-scale women’s participation in combat – probably the largest such case in modern history.

The overriding impression left by the case is that women performed a very wide range of combat tasks and “proved themselves” in those tasks, eventually gaining the “acceptance and even admiration” of Soviet military men who had been “initially skeptical or hostile.” I will summarize each of the main areas in which women took part, in rough order of the importance of female participation to that area – front-line medical support, antiaircraft, combat aviation, partisan forces, infantry, and armor.16

Medical support tasks in the Soviet military were integrated with combat to an unusual degree. Doctors and nurses served at the front lines under intense fire. All nurses and over 40 percent of doctors in the Soviet military were women. Many of the heroic stories about these women – some of which appear to be true even if some are exaggerated – revolve around their actions in dragging and carrying wounded male soldiers to safety on the battlefield, sometimes by the dozen. In other cases, women medical soldiers joined and even commanded infantry units when the male ranks were decimated. Reportedly, Vera Krylova enlisted as a student nurse in 1941, was sent to the front, and dragged hundreds of wounded comrades to safety under fire. When her isolated unit was ambushed and its leaders killed, in the chaos of the German advance of August 1941, the wounded Krylova jumped on a horse, took command of the company, and led a two-week battle through encircling enemy forces to rejoin Russian forces. The next year, fighting with a different unit which was retreating from a tank battle, Krylova moved forward to collect hand grenades from wounded comrades being left behind, then single-handedly charged the German tanks with grenades, slowing the advance enough for the Russians to evacuate their wounded. Such tales, although not verifiable in particular cases, reflect an overall reality – that many thousands of Soviet women served as front-line medical workers and some also participated directly (and effectively) in combat.17

Antiaircraft units were staffed and commanded entirely by women – apparently hundreds of thousands in all. (British forces in World War II included women in antiaircraft units but had men fire the guns. US home-territory antiaircraft defense, though not needed in the end, also relied on women.) One German pilot is quoted as saying that he would rather fly ten times over hostile Libya than “pass once through the fire of Russian flak sent up by female gunners.” One reason cited for the women’s success was that, in these all-female military units, a “military female subculture” emerged which did its work in a warmer and more casual way than in men’s units.18

In the Soviet air force, three women’s regiments were formed – a small fraction of the total force but a useful test of all-female combat units. The women pilots were organized by Marina Raskova, a kind of Amelia Earhart celebrity in the Soviet Union in the 1930s, who was flooded with offers by women pilots to volunteer in World War II. She convinced Stalin of their potential value in the war effort, and went on to organize the regiments and lead one of them until her death (at age 31) in a crash en route to their first deployment in 1943.19

The most famous was the 588th Night Bomber Air Regiment (46th Guards Bomber Regiment), sometimes called the “night witches.” It had over 4,000 members, and at its peak carried out hundreds of sorties per night (officially, 24,000 missions in all). These pilots flew cheap, combustible biplanes (see Figure 2.2) – often unarmed, sometimes armed with a light machine-gun in back, to drop bombs on German positions at night (they could not have survived in daytime). They suffered substantial losses. Although the plane could land almost anywhere, the crew did not have parachutes, so a fire was often fatal. At dusk the women would fly from a rear base to a temporary airfield near the front, then send one plane every three minutes out to and back from the target all night long, with each plane completing up to three missions in one night. The system provided the Germans with no rest at night, but also let them anticipate the arrival of a plane and catch it in spotlights, making it an easy target. The pilots learned to slip-slide out of the spotlights and make their bombing runs with engines turned off until after they had dropped their six to eight bombs. Especially in winter, when nights were longest, “[t]he women – pilots and ground crews alike – lived on the verge of physical collapse, managing a bit of sleep or a meal whenever they could.”20

Figure 2.2 Soviet night-bomber flown by women pilots, World War II. [Photo by Yevgeny Khaldei, courtesy of Anne Noggle.]

The unit was the only truly all-female one – not only pilots and navigators but also most of the ground crew (e.g., mechanics and bomb-loaders) were women. (The other two regiments were commanded by males who replaced the original women leaders, when Raskova died and another commander was recalled for ill health. The appointment of male commanders seems to have been an expedient measure under time pressure to get the regiments into service.) The night bomber regiment was famous during the war, receiving extensive domestic and international press.

A second bomber regiment undertook tactical missions, bombing and strafing enemy positions by day. Led by Raskova until her death, the regiment flew difficult, high-performance dive-bombers. Some of the ground crew, and some tail-gunners, were men, but all the pilots and navigators were women. Unlike the night bombers, this regiment received very little publicity during the war and operated under virtually the same conditions as the equivalent male bomber regiments. The commander said: “During the war there was no difference between this regiment and any male regiments. We lived in dugouts, as did the other regiments, and flew on the same missions, not more or less dangerous.”21

The third regiment was an interceptor unit (the 586th). Also commanded by a man, it eventually incorporated a male squadron (ten planes) to join the two female squadrons. Some of the ground crew were men, mainly because the sophisticated aircraft required skills beyond the rudimentary training of most women mechanics at that time. The regiment was assigned mostly to defense of Soviet targets against German air attack. Its role was to drive away attacking planes rather than pursue them. Therefore it recorded relatively few “kills.” In one episode recounted first-hand, two women pilots of this regiment (in two planes) boldly attacked straight into the middle of 42 German bombers defended with machine guns, shooting down four and turning back the rest before being forced down. Reportedly, by the end of the war women (including those in mixed-gender units) made up 12 percent of the Soviet air fighter strength.22

Some individual women pilots also served in mostly male units. Raskova’s attempt to gather women aviators together did not entirely succeed. In 1942, eight women from the interceptor regiment were detached and assigned to male interceptor regiments to help in the Battle of Stalingrad. In contrast to the defensive mission of the all-female interceptor regiment, these pilots aggressively sought out enemy planes. Two of these women became “aces,” each credited with about a dozen kills. One of them, Lilya Litvyak, was known as the “White Rose of Stalingrad.” In her perhaps-too-perfect story, the heroine starts as the “wingman” (supporting plane) to a male pilot, falls in love with him, is filled with fervor after his death, gets shot down multiple times, and is ultimately ambushed by eight German fighters at once, with her wreckage lost (it was reported found in 1989).23

In the partisan forces – irregular guerrillas who operated in and around areas under German occupation – women played an important role, though not in all-female units. By one estimate, about 27,000 women participated, making up over 8 percent of the total partisan forces (and 16 percent in the partisan stronghold of the Belorussian forests). The women performed various tasks, mostly “medical, communications, and domestic chores; but all were armed, and many fought.” The extent of women’s participation, and the degree of (“clearly romanticized”) gender equality within the partisans, seem to have varied from place to place. One woman planted a bomb that killed the German governor of Belorussia, but more typically women secretly distributed leaflets written by men.24

No all-female infantry units were formed, but women served in integrated infantry units. Several hundred thousand received training in firing mortars, machine-guns, and rifles. A special school was established in 1943 which trained hundreds of women snipers. They “performed well” (except in throwing hand grenades and climbing trees). One woman killed off an entire German company over 25 days, and another was decorated for killing over 300 German soldiers. Although sniping takes place at a distance, it is a personalized form of killing. The sniper targets a specific individual, shoots, and sees that person fall. Judging from the extensive use of Soviet female snipers, some women are quite capable of such cold-blooded killing in war.25

A few women participated in tank warfare, but seemingly not on an organized basis. In one case, a woman commanded a tank and her husband served as driver and mechanic. In another famous case, a woman whose husband was killed in action bought her own tank, named it the “Front-line Female Comrade,” and was killed in a tank battle.26

Overall, in Soviet forces during World War II, “women proved of equal competence in those few moments when a fluid situation and the force of circumstances threw them into a central role.” They performed a wide variety of combat tasks effectively. It is difficult to discern the overall picture amidst the romantic propaganda, and the record is complex. For example, German sources sometimes were contemptuous of Soviet women’s ability and willingness to fight, while at other times they gave grudging respect to Soviet women fighters they had faced. The Soviet Union, faced with a dire emergency, mobilized women extensively into military tasks for which the culture had afforded them little experience and few scripts to follow. Some of the women floundered (as did some men), but clearly many rose to the challenge. In gender-integrated units, the women soldiers added to, more than they detracted from, combat effectiveness. This is why women kept being sent to those units. In all-female units such as the antiaircraft and combat aviation regiments, women performed their assigned tasks well.27

The Soviet case, thus, underscores the lesson of the Dahomey Kingdom, that women can be organized into effective large-scale military units. In neither case were women the majority, but in both cases the mobilization of a substantial minority of women soldiers increased the state’s military power.

However, the Soviet case also underscores how extreme the threat to a society must be before it will use women in combat (see pp. 10–22). The Soviet Union of World War II – invaded, occupied, its cities decimated and besieged, its people starving – still mobilized over 90 percent men. Its women soldiers were rarely assigned to ground combat roles and, like today’s American women soldiers, fought mainly when circumstances thrust them into the line of fire. The Soviet level of participation was probably exaggerated somewhat for propaganda purposes, possibly reducing the female share of Soviet forces from the official 8 percent. Even that level of participation occurred only in the Soviet Union, of all World War II belligerents – a society that preached (albeit, hardly practiced) gender equality, and which had already integrated women into many traditionally male industrial jobs. None of that takes away from the main conclusion of the case, however: women participated in combat in large numbers, and their participation added to the Soviet Union’s military strength. Hundreds of thousands of women made good soldiers.

Contrast with Nazi Germany Despite the cases of Dahomey and the Soviet Union, not every society obsessed with war, or even desperately fighting for its survival, allows women into combat. For example, Germany in World War II contrasts with the Soviet Union. Germany’s position in both World Wars would seem to favor reliance on women, since Germany faced chronic shortages of “manpower” (lacking, among other things, the colonial populations of Britain and France). In World War I, when the expected quick victory turned to protracted war, German women entered industrial jobs (about 700,000 in munitions industries by the end of the war), and served as civilian employees in military jobs in rear areas (medical, clerical, and manual labor; women trained for jobs in the signal corps late in the war but never deployed). German women won the vote after World War I, and some kept their jobs in industry.28

However, the Nazi ideology promoted a gender division, with women assigned to the home and the production of German children, while the men engaged in politics and war. Therefore Germany went into World War II with a different gender ideology than the Soviet Union, one much less conducive to the participation of women in war. Given a labor shortage, which became more severe during the war, Nazi Germany did draw on the work of women, but in ways that kept them away from combat, at least until the final collapse. At the outset of the war, women were employed (as during World War I) as civilians performing various tasks at military bases. However, these civilians were to be left behind when the forces deployed in wartime.29

The labor needs created by the war, especially as Germany found itself administering a large territory that it had rapidly conquered, led to the creation of a women’s Signal Auxiliary of radio and telephone operators (picking up from the underused World War I signal corps women). It had about 8,000 members in the second half of the war. A Staff Auxiliary allowed about 12,000 women to carry out about one-third of the higher-level clerical jobs in rear areas throughout occupied Europe. The air force made most extensive use of women in an Auxiliary role – 100,000 by the end of the war. Most performed clerical, communications, and weather-related tasks, but many worked in antiaircraft units – not working with guns but staffing searchlight batteries (15,000 women running 350 batteries) and similar functions.30

All these uses of women by the Nazi military aimed to free men soldiers for combat while rigidly separating women from combat. Even the women’s auxiliaries – who served in uniform, with rank, and under military discipline – “were neither trained in the use of arms nor were they allowed, under any conditions, to use them,” even as a last resort to prevent capture. (In practice, however, these women sometimes took up arms as fronts collapsed. Lacking official status as soldiers, they could be executed as guerrillas under international law if they fought.) German military leaders were “horrified” at the Soviets’ use of women soldiers, and resisted arming women even late in the war as manpower demands became extreme. In the last months of the war, Hitler reluctantly authorized creation of an experimental women’s combat battalion, and later a mixed-gender guerrilla organization, but neither unit was deployed before the end of the war.31

The key factors that apparently opened the door for Soviet women in combat were desperation, total militarization of society, and an ideology that promoted women’s participation outside of traditional feminine roles. Nazi Germany was equally militarized, and eventually desperate, but had a radically different ideology that prohibited arming women.

Other cases

Several other historical cases show the potential to use women’s units in combat. These cases generally are smaller scale and of shorter duration than the Dahomey and Soviet cases.

Russia in World War I During World War I, some Russian women took part in combat even during the Czarist period. These women, motivated by a combination of patriotism and a desire to escape a drab existence, mostly joined up dressed as men. A few, however, served openly as women. “The [Czarist] government had no consistent policy on female combatants.” Russia’s first woman aviator was turned down as a military pilot, and settled for driving and nursing. Another pilot was assigned to active duty, however.32

The most famous women soldiers were the “Battalion of Death.” Its leader, Maria Botchkareva, a 25-year-old peasant girl (with a history of abuse by men), began as an individual soldier in the Russian army. She managed (with the support of an amused local commander) to get permission from the Czar to enlist as a regular soldier. After fighting off the frequent sexual advances and ridicule of her male comrades, she eventually won their respect – especially after serving with them in battle. Botchkareva’s autobiography describes several horrendous battle scenes in which most of her fellow soldiers were killed running towards German machine-gun positions, and one in which she bayoneted a German soldier to death. After two different failed attacks, she spent many hours crawling under German fire to drag her wounded comrades back to safety, evidently saving hundreds of lives in the course of her service at the front. She was seriously wounded several times but always returned to her unit at the front after recuperating. Clearly a strong bond of comradery existed between her and the male soldiers of her unit.33

After the February 1917 revolution, Alexander Kerensky as Minister of War in the provisional government allowed Botchkareva to organize a “Battalion of Death” composed of several hundred women. The history of this battalion is a bit murky because both anti- and pro-Bolshevik writers used it to make political points. (By contrast, the earlier phase of Botchkareva’s military career is more credible.) Botchkareva’s own 1919 account was “set down” by a leading anti-Bolshevik exile in the United States, who says he listened to her stories in Russian over several weeks and wrote them out simultaneously in English. The narrative is just a bit too politically correct (for an anti-Bolshevik); the stories of her heroic deeds are a bit too consistently dramatic. The language and analysis at times do not sound like the words of an illiterate peasant and soldier, and the book explicitly appeals for foreign help for Russian anti-Bolsheviks. (Louise Bryant’s pro-Bolshevik account is equally unconvincing.)34

Botchkareva was aligned with Kornilov’s faction, which wanted to restore discipline in the army and resume the war against Germany, contrary to the Bolshevik program of ending the war and carrying out immediate land reform and seizure of factories at home. During mid-1917, army units elected “committees” to discuss and decide on the unit’s actions. Botchkareva insisted on traditional military rule from above in her battalion, and got away with it (though with only 300 of the original 2,000 women) because the unit was unique in the whole army. This endeared Botchkareva to many army officers and anti-Bolsheviks. It also put her battalion at the center of the June 1917 offensive – she says that it was the only unit capable of taking offensive action.

The battalion was formed in extraordinary circumstances, in response to a breakdown of morale and discipline in the Russian army after three horrible years of war and the fall of the Czarist government. By her own account, Botchkareva conceived of the battalion as a way to shame the men into fighting (since nothing else was getting them to fight). She argued that “numbers were immaterial, that what was important was to shame the men and that a few women at one place could serve as an example to the entire front….[T]he purpose of the plan would be to shame the men in the trenches by having the women go over the top first.” The battalion was thus exceptional and was essentially a propaganda tool. As such it was heavily publicized: “Before I had time to realize it I was already in a photographer’s studio…. The following day this picture topped big posters pasted all over the city.” Bryant wrote in 1918: “No other feature of the great war ever caught the public fancy like the Death Battalion, composed of Russian women. I heard so much about them before I left America….”35

The battalion began with about 2,000 women volunteers and was given equipment, a headquarters, and several dozen male officers as instructors. Botchkareva did not emphasize fighting strength but discipline (the purpose of the women soldiers was sacrificial). Physical standards for enlistment were lower than for men. She told the women, “We are physically weak, but if we be strong morally and spiritually we will accomplish more than a large force.” She was preoccupied with upholding the moral standards and upright behavior of her “girls.” Mostly, she emphasized that the soldiers in her battalion would have to follow traditional military discipline, not elect committees to rule as the rest of the army was doing. “I did not organize this Battalion to be like the rest of the army. We were to serve as an example, and not merely to add a few babas [women] to the ineffective millions of soldiers now swarming over Russia.” When most of the women rebelled against her harsh rule, Botchkareva stubbornly rejected pleas from Kerensky and others – including direct orders from military superiors – to allow formation of a committee. Instead she reorganized the remaining 300 women who stayed loyal to her, and brought them to the front, fighting off repeated attacks by Bolsheviks along the way. The battalion had new uniforms, a full array of war equipment, and 18 men to serve them (two instructors, eight cooks, six drivers, and two shoemakers).36

The battalion was to open the offensive which Kerensky ordered in June 1917. (Since the February revolution, there had been little fighting and growing fraternization on the Russian–German front.) The Bolsheviks opposed the offensive, and the tired, demoralized soldiers were not motivated to participate in it. By sending 300 women over the top first, Botchkareva envisioned triggering an advance along the entire front – 14 million Russian soldiers – propelled by the men’s shame at seeing “their sisters going into battle,” thus overcoming the men’s cowardice. When the appointed time for the attack came, however, the men on either side of the women’s battalion refused to move. The next day, about 100 male officers and 300 male soldiers who favored the offensive joined the ranks of the women’s battalion, and it was this mixed force of 700 that went over the top that night, hoping to goad the men on either side into advancing too. Locally, the tactic worked, and the entire corps advanced and captured three German lines (the men stopping at the second, however, to make immediate use of alcohol found there). As the Russian line spread thin, however, another corps which was supposed to move forward to relieve them refused to advance. A costly retreat to the original lines ensued. The shame tactic had failed, except for a local effect, which anyway may have been caused as much by seeing comrades under fire as by feeling shame about women going first. Ultimately, Botchkareva concludes about the Russian army, “the men knew no shame.”37

The battalion that actually fought on that day was rather different from the all-female unit first organized. The battalion arrived at the front with 300 women and two male instructors. Before battle, it received 19 more male officers and instructors, and a male “battle adjutant” was selected. During final preparations, a “detachment of eight machine guns and a [male] crew to man them” were added. Lined up in the trenches for the first night’s offensive that did not materialize, six male officers were inserted at equal intervals, with Botchkareva herself at one end and her male adjutant in the center. In the force that actually went over the top the next night with 400 male soldiers and officers added, the “line was so arranged that men and women alternated, a girl being flanked by two men.” Botchkareva notes that in advancing under withering fire, “my brave girls [were] encouraged by the presence of men on their sides.” Although the women fighters clearly were brave, and one-third of them were killed or wounded, their effect (and indeed their purpose) lay not in their military value – 300 soldiers could hardly make a difference among millions – but in their propaganda value. However, this latter effect did not materialize as hoped.38

Other women’s battalions were formed in several other cities – apparently less than 1,000 women in all – but they suffered from a variety of problems, ranging from poor discipline to a lack of shoes and uniforms. These other units never saw combat. There was not another offensive before the Bolsheviks took power in October and sent most of the women soldiers home, telling them “to put on female attire.”39

The Battalion of Death, then, never tested an all-female unit’s effectiveness in combat. Nonetheless, on one day in 1917, 300 women did go over the top side by side with 400 male comrades, advanced, and overran German trenches. The women apparently were able to keep functioning in the heat of battle, and were able to adhere to military discipline. These women were, of course, an elite sample of the most war-capable women in all of Russia. Nonetheless, they did it – advanced under fire, retreated under fire, and helped provide that crucial element of leadership by which other nearby units were spurred into action, overcoming the inertia of fatigue and committee rule. The Battalion of Death did this not as scattered individual women but as a coherent military unit of 300 women – instructed by Botchkareva that “they were no longer women, but soldiers.”40

Taiping Rebellion and other cases Very occasionally, all-female military units have cropped up elsewhere in the world for short periods of time. In the nineteenth-century Taiping Rebellion in China, the rebels formed and then later disbanded female units in their army. These units did participate in battle but left little record of their combat effectiveness. The rebellion – a massive uprising led by a Christian cult leader, with roots in the Hakka ethnic group of southern China – became perhaps the bloodiest civil war in history (tens of millions killed). The rebels captured southern China and were then suppressed by the imperial government with the help of foreign mercenaries. The Taipings’ puritanical religious doctrine called for rigid gender separation, with men’s and women’s quarters in cities, and even married couples faced execution if found together. This segregation was abandoned after several years owing to its bad effect on morale (especially since it had never been followed by top leaders).41

Rumors of female armies in ancient China are murky. I have been unable to find any historically documented cases. In times of siege, units of women, of children, and of old men were formed to help with defense, but in support rather than combat roles. The Cambridge History of China makes a passing reference to China’s frontier region in the second century AD where “even Chinese women had been transformed into fierce warriors under the influence of the Ch’iang” ethnic group. The book’s description of the Ch’iang does not mention women fighters, however. The war participation of women in second-century China, whatever its extent, appears to reflect the Wild West character of the region rather than the incorporation of women en masse in a regular army.42

Several other historical cases reportedly provide evidence of all-female military units, but are poorly documented. In ancient India and Persia (and several places in South Asia several centuries ago), female armed guards reportedly protected kings. A Chinese art historian states that the Hsi-hsia army – in a non-Chinese state northwest of the Song dynasty in the eleventh to thirteenth centuries – used female shock troops and had a tradition of female warriors going back hundreds of years. Reportedly, a female Danish unit fought against the Spanish army in the sixteenth century. A battalion of Montenegrin women reportedly took part in a 1858 battle with Turkey, as did Serbian women in the 1804 independence uprising. In the Congo in 1640, the Monomotapa confederacy supposedly had standing armies of women. The first army in postcolonial Malawi in 1964 reportedly included an elite unit of 5,000 women to guard the Tanganyikan border. (Shaka Zulu’s army by one erroneous account had an all-female front-line regiment. Scholarship on Shaka’s military tactics makes clear that all the soldiers were men.)43 |

| |

| B. MIXED-GENDER UNITS |

In addition to the extremely rare cases of all-female military units, evidence of women’s combat potentials appears in cases where mixed-gender military units have engaged in combat. Although main combat-designated units are nearly always all-male, some units not designated primarily for combat have included women, in a variety of cultures and time periods. These units, trained in the use of arms, sometimes find themselves engaged in combat, with the women participating. We have evidence from guerrilla organizations, from the few NATO countries that currently allow women into combat positions, and from the present-day US experience with gender integration.

Guerrilla armies

Guerrilla warfare provides a rich source of data on mixed-gender combat units. Women fighters are not uncommon in guerrilla armies (see Figure 2.3). From the Cold War and post-Cold War eras alone, scholars have illuminated women’s crucial roles in a variety of wars, including in Vietnam, South Africa, Argentina, Cyprus, Iran, Northern Ireland, Lebanon, Israel, Nicaragua, and others.44

Figure 2.3 Kurdish women guerrillas, 1991. [AP/Wide World Photos.]

In World War II, in addition to the Soviet partisans (see pp. 000–000), women participated in the partisan forces of other occupied countries as well – countries that did not allow women into regular military forces – including Italy, Greece, France, Poland, and Denmark. They took part in street fighting, carried out assassinations, and performed intelligence missions. In Italy, reportedly 35,000 women were partisans, of whom 650 were killed. In the French Resistance, women were much more excluded from combat roles (although they played many dangerous support roles). Only a few women were “full-time, gun-carrying women fighters.” Because of prejudice in France against women fighters, one of the few women who had a leadership position in combat often pretended to be a representative of a male leader when organizing the Resistance. Another was excluded from participating in armed attacks because the uniformed army of de Gaulle opposed giving guns to women, even though local Resistance men considered her an equal comrade.45

Most notable among the World War II women partisans were those of Yugoslavia, a country where centuries of tradition allowed some role for women as fighters, and where conditions were nearly as desperate as in the Soviet Union. Most women’s work in the mass resistance to Nazi occupation was in traditionally feminine support roles. Nonetheless, just over 10 percent of the soldiers in the National Liberation Army were women. They received the same kinds of minimal basic training as men (but first aid or medical training more often than men), and the official communist ideology declared them equivalent. In practice, women tended to remain at low ranks and to be concentrated in medical tasks. In one set of units studied, 42 percent of the women were “fighters” and 46 percent medics. “Clearly, the role of medic became ‘feminized’…[I]f there was a single woman in the [unit], she would be designated the medic.” Nonetheless, in guerrilla war even medics are usually fighters too. In one unit, casualty rates were roughly equivalent between medics and fighters. “Women partisans led the same life as men – they slept in the same quarters, ate the same food, and wore the same clothes.” The partisan force “severely discouraged” sexual relations in the ranks, although arrangements were made for married couples.46

Accounts of the effectiveness of the women soldiers, even taken in the same cautious vein as the Soviet case (with allowance for propaganda distortion), suggest that women made an important contribution overall. By official count, 100,000 women were in the National Liberation Army and partisan units so thousands must have been fighters. Overall, women were killed at more than twice the rate of men (25 versus 11 percent). Despite the limits on their participation, the women of the Yugoslavian resistance acquitted themselves well in combat, showing above-average bravery and stamina. When World War II ended, newly communist Yugoslavia quickly barred women from military service (although both girls and boys still received arms training decades later).47

The Vietnamese communists’ war against the French and Americans shares several features with the World War II Yugoslavia case – a communist-led “people’s war” in a country with some tradition of women warriors (see the Trung sisters, p. 121). This tradition was updated, in the “war of liberation” (1946–75), to the picture of a Vietcong woman with a baby in one arm and a rifle in the other. As in Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, the image of women fighters symbolized the mobilization of the entire society for the cause. Behind the image, propaganda aside, was a hard reality of women’s participation. One Vietnamese military historian estimates that 60,000 women were in the regular forces, over 100,000 in the volunteer youth corps, and over 1 million in militias and other local forces. In the People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF) in the 1960s, a woman veteran of local uprisings was appointed deputy commander, and by one estimate 40 percent of all regimental commanders were women. The women soldiers served in both all-female and mixed-gender units. Reportedly, the latter experienced some problems regarding male attitudes, and the men often considered the women inferior in combat. Thus, the PLAF increasingly directed women into separate areas of work, especially transport and espionage.48

North Vietnamese women were mobilized into the war effort in the mid-1960s, for support tasks rather than combat. Even those within the army itself mainly worked on medical, liaison, antiaircraft, or bomb-defusing tasks. “It was general policy to discourage active combat for women.” Women did serve in local militia units in the North – working in the fields with rifles slung over their shoulders – but these areas were far from the “front.” Nonetheless women in the North played an important part in shooting down US airplanes and capturing pilots. In the South, meanwhile, more women were recruited by the communist army, but mainly for support functions. Women did apparently participate in combat during the 1968 Tet offensive. But as guerrilla war gave way to conventional war, women were separated more from combat. “In the end, the role of women in the Vietnamese revolution was a significant but somewhat restricted one.” (In the South Vietnamese government army, some women also fought.)49

Ideals of motherhood and feminine duty supported participation in the North Vietnamese war effort. Women participants in the war effort experienced it not in terms of glorious exploits but as a huge added burden on an already full basket of “women’s work.” Women carried most of the loads along the Ho Chi Minh trail to sustain the war effort. Although they might take part in fighting, especially in antiaircraft defense of their home communities, women’s main function in the war was to provide cheap labor. Women’s combat participation, although glorified during the war as a model of self-sacrifice for the nation, was downplayed and largely forgotten after the war, as in other countries.50

The image of the woman holding a rifle and a baby is found in liberation movements across the third world. It combines the roles of motherhood and war, harnessing women for war without altering fundamental gender relations. Cynthia Enloe finds in the image an expectation that, after the war ends, mothers will put down the rifles while keeping the babies. She asks: “Where is the picture of the male guerrilla holding the rifle and baby?”51

The Sandinistas of Nicaragua resemble the other communist revolutionary guerrillas. Women reportedly made up nearly one-third of the Sandinista front’s military. After victory, the front’s founder praised women for being “in the front line of battle.” Women were particularly attracted to the Sandinista front because, as a movement that grew up in a feminist era, the front had a strong women’s organization which advocated policies that helped women. Nonetheless, after victory, the “defense of women’s role in the military failed. After their victory in July 1979, most women were demobilized, and the rest were placed in all-female battalions.” The director of Nicaragua’s leading military school explained the “need to train women separately” as being “not because of any limitations the women have. In fact, you might say it’s because of failings on the part of some men….[who] aren’t always able to relate to a woman as just another soldier.” However, apparently exceptions were made for women of superior military skill, who remained in their male army units. Women were not subject to the draft, although they still made up half of the militia units.52

In some ways, the Sandinistas left traditional gender roles firmly in place. Women were mobilized around the image of mothers protecting their children as part of a divine order. One Sandinista official said in 1980, “give every woman a gun with which to defend her children.” In fact, however, good mothers were expected to be “Patriotic Wombs” that would provide soldiers for the revolution and happily send them off to die for the cause. The Sandinistas limited abortion and sterilization, among other measures to produce high birth rates, since a small nation at war needed more people. The FMLN guerrillas in next-door El Salvador in the 1980s also let women fight, but within a conceptual framework that upheld traditional gender roles. Cynthia Enloe highlights the story of a woman FMLN guerrilla in El Salvador who, with the end of the war there, is having her IUD removed – a transition from soldier to mother.53

In Africa, women guerrillas also have fought and then been pushed aside. For example, Joice Nhongo was the “most famous” guerrilla in the ZANLA forces that overthrew white rule in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). She was known as “Mrs. Spill-blood Nhongo,” and gave birth to a daughter at the camp she commanded, two days after an air raid against it. After ZANLA took power, she became Minister of Community Development and Women’s Affairs – safely removed from military affairs. (Reportedly, 4,000 women combatants made up 6 percent of ZANLA forces.54)

In South Africa in the 1980s, the armed wing of the African National Congress included women guerrillas. Thandi Modise was called the “knitting needles guerrilla” because she carried a handbag with a protruding pair of knitting needles while traveling incognito. She reports that in training camps, the women (under 10 percent of the trainees) received the same uniforms and training, and were treated respectfully, as equals, by the men. She sees no contradiction in being a guerrilla and a mother, and argues that “Marriage and children are necessities, not luxuries.” Modise does, however, say that “As a woman I tried to avoid killing people.” Although male and female guerrillas received the same training, side by side, and women sometimes outdid men in discipline, sharpshooting, and running, women were excluded from traditional combat roles. As a male guerrilla put it, “Yes, a woman can be a soldier. Many women fight better than men. But I wouldn’t deploy women in the front line…. Men go to war to defend their women and children.” Manliness played an important role for South African black male guerrillas, and even Nelson Mandela once said that the “experience of military training made me a man.”55

It is not only in communist revolutionary movements, such as in Yugoslavia, Vietnam, and Nicaragua, that women participate in local militias. This phenomenon is widespread, because militias often constitute a last line of defense of home and family against external attack. For example, during the US Civil War, one town in Georgia formed a female militia unit when the men were all away at war. They drilled, practiced shooting, and in an “apocryphal story” supposedly faced down Sherman’s cavalry which had planned to burn the town.56

In Sri Lanka currently, women apparently constitute about one-third of the rebel Tamil Tigers’ force of 15,000 fighters, and participate fully in both suicide bombings and massacres of civilians. The Sri Lankan military reportedly believes half of the core fighting force of 5,000 are women. (A claim that women are two-thirds of the force appears to be overstated.)57

In Iraq in the late 1990s, one of the main guerrilla groups operating against next-door Iran – with 30,000 soldiers, Iraqi backing, and $2 billion worth of weapons – is led by a 43-year-old Iranian woman and her husband. She is the “symbol of the struggle” and their candidate for transitional President of Iran if they should ever seize power. Reportedly, the group is led by mainly female officers, and includes women among its fighters – although how many women is unclear. Members live in gender-segregated quarters and married couples suspend marriages to function as “sisters and brothers” in the group. The force engaged in combat in 1988, and 1991, and reportedly performed well.58

The greater fluidity of gender roles in guerrilla as compared with conventional war is illustrated by the Republic of Congo war in 1997. Guerrilla militias included women fighters and commanders. Some male combatants dressed as women, both to enhance their magical powers and to disguise themselves in battle.59

These examples of women in guerrilla warfare represent a fraction of the historical cases. In guerrilla war, by contrast with conventional war, women’s participation is not rare. One often finds combat units with a nontrivial minority of women in the ranks. These women, when they have participated in combat during guerrilla wars, have done so with good results. They have added to the military strength of their units, and sometimes fought with greater skill and bravery than their male comrades. Yet whenever their forces have seized power and become regular armies, women have been excluded from combat. Evidently, this exclusion is not based on any lack of ability shown by the women soldiers when they participated in the guerrilla phase of war.60

Present-day state armies

More than a dozen states – mostly industrialized countries that are US allies – currently allow women into official combat positions. The exact number depends on how exactly one defines combat. A 1993 list includes Canada, Belgium, Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, and Britain. A 1997 work also includes Spain and Australia, but not Britain. By 1999, in addition, France, Japan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Israel, and Russia had at least one woman fighter-jet pilot, and women served in navies in Portugal, South Africa, and others. In 2000, an Israeli law and a German court ruling promised to integrate women into more military jobs, though implementation is unclear and ground combat will likely remain off-limits.61

Eritrea and South Africa had women in the infantry, owing to the recent integration of former guerrilla forces into state armies there. Eritrean women combatants have seen extensive combat – uniquely among present-day state armies – owing to the highly lethal ground war with Ethiopia in the late 1990s. Some reports put women at one-third of Eritrean combat forces. Eritrea, however, has existed as a state for only a few years, and is still led by former guerrilla commanders, even though fighting a conventional, not guerrilla, war.62

Women’s status in NATO militaries is evolving year by year, with the policies and numbers shifting continually towards greater women’s participation. The different countries are generally moving along a common path in integrating women, though at different speeds – from combat aviation, to combat ships, to submarines, to ground combat. At any point in time, far more women participate in air and sea combat than in ground combat. Women in all these positions total only a few thousand (out of millions of combat soldiers today), but they provide further data points to assess the performance of women in combat. Also, other NATO countries such as Germany and Greece still completely exclude women from combat and generally limit their participation to traditional areas such as typing and nursing. Overall, women’s participation has been recent and the units in which they serve have seen little if any combat since being integrated. Women aviators did, however, participate in NATO’s 1999 air campaign against Serbia.63

Canada is furthest along the spectrum of NATO countries. Canada’s military has opened all positions to women, in theory. Furthermore, the military is actively recruiting women interested in serving in ground combat positions. New submarines are being built to accommodate women. Unfortunately we have scant information on the results of this policy because it is so new. Canadian units have not seen combat since women joined them, although they have deployed on at least ten peacekeeping missions around the world. In the Gulf War, women served on a Canadian supply ship, but only 3 percent of Canadian forces participating in that war were women, compared with over 10 percent in the Canadian military overall at that time. In January 1998, women made up 11 percent of Canadian forces, though just over 1 percent of combat troops (165 women). Sexual harassment and rape are serious problems in the gender-integrated Canadian military, and female soldiers “are often little more than game for sexual predators,” according to one recent exposé. An official army study in 1998 “said women in combat units commonly were referred to in coarse sexual terms.”64

Denmark, Norway, and France are nearly as gender-integrated as Canada. Danish women serve in tank crews, including those that were deployed for peacekeeping in Bosnia. (Although peacekeeping is not usually “combat,” Danish tanks had earlier battled Bosnian Serb forces.) Denmark’s decision to include women in all military roles resulted from extensive trials in the mid-1980s to find out how women performed in various land and sea combat roles. “The trials proved very satisfactory, and today all functions are open to women…. The trial results [show]….that women can do the work just as well as their male colleagues.”65

France allows women in air, sea, and ground combat, and plans to subject women to the draft starting in 2001. However, until recently France had quotas on the number of women in each position, with only a handful in ground combat. Women are still not allowed in the Foreign Legion, commando positions, or flying naval airplanes, although they no longer face quotas in other positions including flying combat aircraft. As recently as 1994, NATO summarized France’s policies on women in combat thus: “A woman’s role is to give life and not death. For this reason alone it is not desirable for mothers to take direct part in battle.”66

In Norway, women serve on submarines, including one as a captain. They are in infantry, artillery, tanks, and all kinds of aircraft. Two served as officers in the UN peacekeeping force in the former Yugoslavia. None of the integrated units has seen combat. Belgium, the Netherlands, and Spain allow women in almost any position in theory, but only a few women serve in practice, especially in ground combat. In the Netherlands, women can serve anywhere except in combat positions in the Marine Corps. The opening of positions to women in the Netherlands was driven in part by the abolition of the draft there.67

Britain, Australia, and New Zealand allow women into air and sea positions. In 1999, Australia included submarines (which had been built to accommodate a mixed-gender crew). Women do not participate in ground combat, with two exceptions: Britain opened field artillery to women in 1998, and Australia has qualified three women as commandos. These forces have not yet participated in combat. The British found in the 1982 Falklands War that it was hard to distinguish “combat” from “noncombat” ships, and this may explain why Britain has opened all surface ships to women (about 700 women serve on British ships currently).68

The Israeli experience In Israel, the persistent myth that Israeli women participate in combat is false. Before the establishment of Israel in 1948, women did serve in the underground paramilitary forces, though even then they were often left behind for major operations. A few women also fought before the 1948 war, when isolated settlements came under attack. With independence and the creation of a regular army, however, women were immediately and permanently excluded from all combat roles. Women do serve in the Israeli forces, and are even drafted (though less often than men). Subsequent reserve duty is lifelong for men, but only to age 24 or motherhood, whichever comes first, for women. Over half of female draftees serve in secretarial and clerical jobs. A women’s corps (its initials spell “charm”) administers the policies concerning Israeli women soldiers, including training them, overseeing their work in various units, and operating some of its own units. A 1980 women’s corps brochure states: “Today’s Israeli female soldiers are trim girls, clothed in uniforms which bring out their youthful” These women serve as “sister-figure” or “mother-figure” in a unit. Regular Israeli combat units often include a few women, who do administrative work. These assignments are “highly sought after” by women. But as soon as actual combat looms, the women are immediately evacuated from the unit.69

In the late 1970s, after the shock of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, and under great manpower pressures, the IDF opened up new nontraditional specialties to women, including instructing men on the use of arms. The 1980 brochure states that women serving as platoon sergeants in all-male basic training “have succeeded outstandingly.” The brochure continues: “New recruits do not dare complain of muscle aches and pains or drop out of a long-distance run when it is being led by a female sergeant.” Women’s success as arms instructors shows that some women can wield weapons effectively – for example, driving tanks, firing guns, and deploying armed groups tactically.70

The reasons given for the exclusion of women from combat in Israel revolve around their effects on male soldiers rather than their own combat abilities. For example, men in mixed units supposedly showed excessive concern for the well-being of the women at the expense of the mission. The actual evidence of such effects is very sketchy, however.71

The US experience

The US military in recent years has compiled the most extensive experience in integrating women into regular military units – though generally not “combat” units. As of 1999, nearly 200,000 women serve in the US military (14 percent of the total force), over 1 million are veterans, and thousands have operated in combat zones in several wars. (Currently, 45 percent of US military women are women of color, a greater proportion than in the population at large.) US women participate in combat support roles, ranging from the traditional (nursing, typing) to the nontraditional (mechanics, arms training). Sometimes the lines between combat and support blur so that women soldiers have found themselves in a combat zone or engaged in fighting.72

Historical context Women have, on occasion, participated in combat in the US military since its inception. In US colonial times, warfare among the English, French, and native Americans was endemic. “For their own survival, colonial women learned to threaten force and to kill in self-defense. Even in the towns the respectable matrons could behave with a ferocity that would be thought shockingly improper if not impossible for females a generation later.” In several historically documented cases, in the countryside women killed American Indians and in towns mobs of women carried out lynchings. During the Revolution, in addition to their roles as camp followers and as soldiers disguised as men, American women fought in militias in the countryside.73

In the Revolutionary War, “Molly Pitcher” is a legendary woman who accompanied her husband in the field – a common practice in armies of the time (see pp. 381–83). She used to nurse wounded troops and carry water (hence her nickname). When her husband was killed in the Battle of Monmouth, she took over firing his cannon – to the admiration of her fellow soldiers – and in a dubious epilogue is said to have met George Washington. (“Molly Pitcher” seems to be a composite of three real women who fought in the war.) In the Civil War, women fought on both sides, most of them disguised as men.74

In World War I, 13,000 women enlisted in the US Navy, mostly doing clerical work–“the first [women in US history]….to be admitted to full military rank and status.” The Army hired women nurses and telephone operators to work overseas, but as civilian employees (although in uniform). Plans for women’s auxiliary corps – to perform mostly clerical, supply, and communications work – were shot down by the War Department. So were plans for commissioning women doctors in the Medical Corps. The end of the war brought an end to proposals to enlist women in the Army.75

In the interwar years, the Army created a Director of Women’s Relations to explain to women, now that they could vote, that pacifism was a bad idea. The embattled Director in the 1920s, Anita Phipps, developed a plan for a women’s corps which would be part of the Army itself, not an Auxiliary, and would incorporate 170,000 women in wartime. This plan was not approved, however. The Army favored keeping any future women workers in an Auxiliary. Even the auxiliary role was approved only because, as an official memo put it in 1941, “it will tend to avert the pressure to admit women to actual membership in the Army.” The same memo declared that the War Department would develop the idea slowly and not rush into it on a large scale.76

The realities of World War II, however, quickly changed this approach. With the United States more deeply mobilized for war (and over a longer period) than in World War I, women’s participation in the military increased dramatically, to about 3 percent of US forces at the peak. The experience of World War II provides the largest amount of information on women soldiers up until the 1980s and 1990s.77

The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was formed early in 1942, soon after Pearl Harbor. In mid-1943 it became a regular part of the Army, as the Women’s Army Corps (WAC). Within the US Army, the incorporation of so many women was an unprecedented development. The WAC encountered serious obstacles in recruiting American women (discussed shortly), and it faced continual bureaucratic attacks from the War Department, the Surgeon General, and others. Mattie Treadwell’s 1954 history tells the story in detail. The WACs were never assigned to combat and rarely got near it. But their large-scale mobilization into the US Army some 65 years ago gives us valuable information about how women perform as soldiers, on some of the dimensions necessary for a functional combat soldier. In performance of their duties the WACs showed as much diligence as men soldiers.

Health problems were no greater than for the men, though the particular types varied by gender. The WACs lost less hospital time than men, and rates of accidents and nonbattle injuries were nearly identical across gender. But men were far more likely to be injured in motor vehicle accidents, whereas women more often fell down in situations unrelated to their jobs – partly because suitable military shoes were not provided. Towards the end of the war, fatigue became a serious problem for WACs, but its character was opposite to the combat fatigue endured by men – for women, it was unrelieved sedentary work with little visible connection to the war effort. Combined with Army food, the sendentary work of WACs led to a “widespread condition of overweight.”78

The WAC found that menstruation presented only minor problems for efficiency, with most of those being caused by Army regulations that, for example, sent women to the hospital for two days if their cramps made them stop work even just long enough for aspirin to take effect. In the Army Air Forces, women who ferried planes were not supposed to fly for several days around their periods, but male commanders found this rule unenforceable since many women did not cooperate with it, said nothing, and just kept flying. (In the event of pregnancy, a WAC was immediately discharged and left to her own resources.)79

In the area of discipline, most of the problems resulted from the novelty of the situation – enforcement varied greatly from one locale to another – and from the men’s problems in dealing with women, such as having “great difficulty in punishing a woman for anything.” Gender differences in discipline may have resulted from the exclusion of WACs from combat as well. As a 1946 Army field manual states, “the necessity for discipline is never fully comprehended by the soldier until he has undergone the experience of battle.” However, overall, morale and discipline were high among the women.80

With regard to their ability to function in a hierarchy (see pp. 206–8), WACs differed from their male counterparts. Curiously, the main difference is opposite to the emphasis on male autonomy and female connectedness discussed earlier (see pp. 46–47). The WAC Director specifically noted that “women need to remain individuals.” This high value on individuality, combined with a lack of experience with loyalty to organizations, made women tend to treat each other as separate individuals, contrary to the military style of hierarchy. If inspired by a WAC leader who set an example of loyalty to the Army, however, WACs’ “natural idealism was apt to produce group loyalty and esprit of an unexcelled intensity.”81

The WACs resented the “caste system” separating officers from enlisted personnel, since it restricted enlisted women’s contact with close friends or family members who were male officers. Within the WAC itself, however, few of the problems experienced in male–male relations across ranks developed. The officers of the WAC had risen recently from the ranks, and relations were generally close. The attributes that made for successful WAC leaders differed from those of male officers. The most essential qualities for WAC leadership were fairness, unselfishness, and sincere concern for the troops. Selfish ambition, accepted in male officers, was “absolutely disqualifying” when leading WACs. Appearance and technical competence, emphasized in training male officers, did not matter for WAC officers. In terms of fitting the WAC into the larger male-dominated Army of which it was a part, few serious problems developed. Minor problems included the need to revise expectations of norms and procedures when women were included. For example, a male officer invited newly arrived WAAC officers to his hotel room for drinks – an action that would have been quite appropriate for newly arrived male officers. The one serious problem in local Army–WAC relations arose in those few cases where a male commander allowed romantic impulses – especially “immoral” ones – to affect military decisions (such as securing special privileges for one WAC). Such cases were viewed as “complete betrayal” by the rest of the WAC unit, and the unit’s effectiveness plummeted.82

WACs were often better than men at communications and clerical work, especially in listening to Morse code for long hours. On the other hand, WACs in the Pacific (where they needed armed escorts to protect them from sex-starved GIs) “became demoralized” by their mail censorship duties which required reading sexually explicit letters home to wives and girlfriends.83

US women also served in the Air Force and Navy during World War II. The Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) worked in ferrying planes and as test pilots. About 1,000 women took part, and 38 died in the line of duty (see Figure 2.4). The Navy WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) participated in air traffic control, naval air navigation, and communications, starting in 1942. There was a Marine Corps Women’s Reserve in both World Wars; 18 died in World War II. They became a permanent component of the Marines, and their successors decades later are described as “even more gung ho than many of the males.”84

Figure 2.4 USWASP pilots after flight in B-17. [US National Archives, 342-FH-4A5344-160449ac.]

At its peak in 1945, the WAC had 100,000 members (at its inception the Army had hoped for 600,000). In all, during World War II, about 150,000 women served in the WAC, nearly 90,000 in the WAVES, about 25,000 in Marine reserves and Coast Guard SPARS, and 75,000 as officer-nurses. Total fatalities appear to be in the range of 200–300 women in all, but apparently few of these were by hostile fire.85

Although soldiers and officers who worked with US military women in World War II adjusted to them and came to value their contributions, public opinion lagged behind. The WAC’s biggest problem was in recruiting, especially after a “slander campaign” against it in 1943. The campaign promoted the idea that WACs were really prostitutes, or women with low morals. Leaders had to spend great energy trying to counteract this campaign both through public advertising and through attention to the women’s appearance (feminine uniforms) and their actual morals, which were generally upstanding. (In the British Army in World War I, officials omitted a breast pocket on women’s uniforms for fear of drawing attention to female anatomy.) Despite efforts to counteract the slander campaign, a survey of Army men in 1945 found that about half thought it was bad for a girl’s reputation to be a WAC. Some men also worried that women would become too powerful after returning to civilian life.86

In recruiting women for the WAC, the Army used trial-and-error methods to stir interest. A major recruiting theme, “Release a Man for Combat,” was abandoned – but could never be fully suppressed in the public mind – when women responded poorly to the notion that their participation could send an American man to his death. Later cheery themes, such as “I’m Having the Time of My Life,” were also unsuccessful. An all-out advertising and canvassing campaign in Cleveland in summer 1943 proved a total failure: personal contact with 73,000 families identified 8,000 eligible women, but brought only 168 recruits. At that rate the 100,000 new WACs needed immediately would require contacting 44 million families, more than the total US population. Waiving the requirement of high school graduation also produced few recruits. As a result of this failure to recruit an additional half-million WACs in 1943, the draft was extended to fathers of young families, even though a March 1944 US poll found that three-quarters of the public would rather draft young single women (for noncombat positions) than young fathers.87

Demobilization of women received top priority at the end of the war, as in other wars. When the war ended, one Navy commander declared, “I want all the women off this base by noon.” After World War II the number of women in the US military dropped drastically, but never back to zero. The World War II experience remained a valuable benchmark of women’s potentials as soldiers, which informed the later integration of women in the US military. In the Korean and Vietnam wars, women’s service as nurses was notable. Recently, a memorial to women veterans has been completed at Arlington National Cemetery, and the history of US women soldiers is becoming better known.88

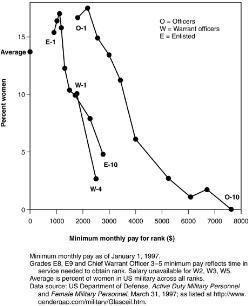

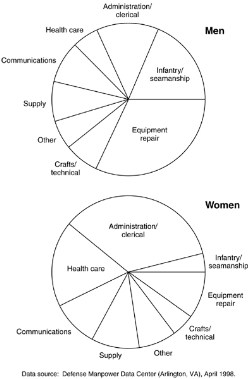

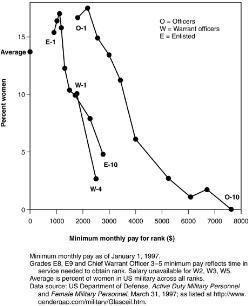

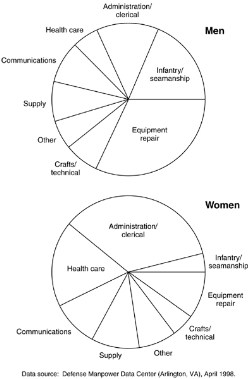

Recent decades